GWMNM private property sign (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Almost all property ownership is conditional, and it always has been. This thousands-of-years-old legal doctrine is seldom appreciated or understood by modern activists, politicians, economists, or even by lawyers.

Some think private property is the cornerstone of civilization. Others criticize the institution of private property, finding in it the root of all evil. They may hold the institution of private property responsible for all manner of social injustices and environmental ills. The alleged evils of private property are often attributed to the underlying legal system in which property ownership is established and enforced. Sometimes it is argued that private property should be abolished and/or that alternative legal frameworks, such as a “law of the commons” need to be established through legislation.

But the law of the commons and the doctrine of conditional ownership are already fundamental parts of our legal system, and have been since remote antiquity, leading me to think that our problems are less structural than maybe cultural or psychological.

It shouldn’t be surprising that political thinkers tend to see remedies to social and environmental problems in political terms, economists in economic terms, philosophers in philosophical terms, and so on, without any of them giving a lot of thought to legal history.

Because the doctrine of conditional property in existing law is so little understood outside a fairly small circle of scholars, and because the commons are constantly being despoiled, privatized, and mismanaged, people tend to assume that our legal framework is deficient in this area. So they naturally assume that we need new laws to protect the commons, rather than looking at existing law and asking why it is under-utilized. But if we don’t understand the the ways that existing law can protect the commons, how will we be able to protect that important part of our legal heritage from attack by corrupt courts and legislatures? And that part of our legal heritage most certainly is quietly under attack, right under our noses. We may loose it before many of us ever even knew it existed.

The confusion about private property ownership is exacerbated by theories about “natural rights” and “natural law”, which have little or no basis in our actual legal system, but belong instead to the theoretical justice systems of philosophers. Natural law (as in philosophy, not natural science) and natural rights theories have been advocated by conservative and liberal thinkers alike, in various historical contexts, to affirm or dispute the authority of kings or governments, and in general to dispute existing laws they didn’t like. Nature’s law (sometimes also mashed up with “divine law”) is different things to different people. Examples can be found in nature for anything from symbiosis to cooperation to violent territorial conquest. Natural law theories are often simply attempts by one group to dispute the prevailing legal authority of another group by appealing to a vague, transcendental authority. Thus natural law theories are now most commonly used by anarcho-capitalists and neo-libertarians to dispute the authority of civil law to regulate their economic activity.

In most Anglo-American jurisdictions, the body of law includes constitutional law and

“statutory law” enacted by a legislature, “regulatory law” promulgated by executive branch agencies pursuant to delegation of rule-making authority from the legislature, and common law or “case law“, i.e., decisions issued by courts (or quasi-judicial tribunals within agencies) (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Common_law#1._Common_law_as_opposed_to_statutory_law_and_regulatory_law)

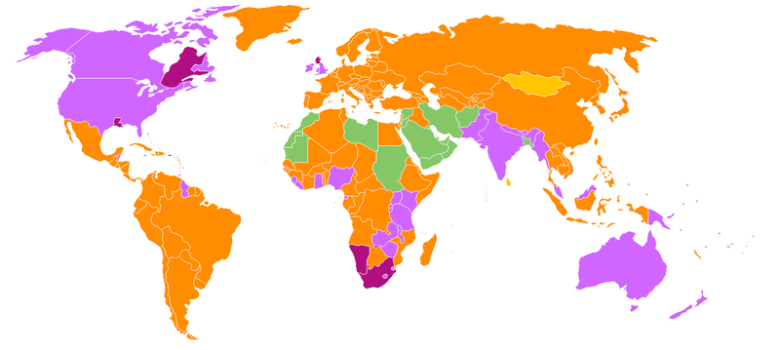

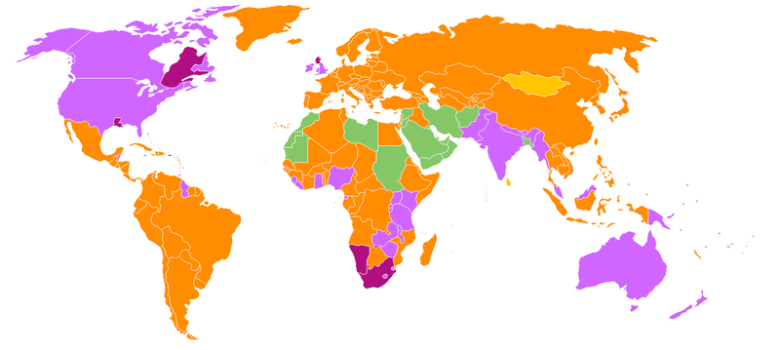

The term “civil law” has several different connotations (one being a distinction from criminal law), but in the map below it is used to mean “a legal system inspired by Roman law, the primary feature of which is that laws are written into a collection, codified, and not (as in common law) determined by judges.” (Wikipedia/Civil law)

Legal Systems of the World (via WikiMedia)

Contrary to the above map, I would characterize the US as a hybrid system of constitutional law, civil law, and common law; but of the three, common law may very well be the most powerful and the least appreciated.

Law in the West may be inspired or influenced by romantic interpretations of nature (the law of the jungle, survival of the fittest); or by ethical, moral or religious teachings; or by scientists, philosophers, economists, politicians, jurists, etc.– but the law is not ruled, over-determined, or limited by any of those influences. Law is a complex bit of sausage-making that has been evolving for thousands of years. We have a legal heritage that one age and culture has passed to the next since even before the times of ancient Greece and Rome. The US, for example, did not start all over from scratch with a brand new legal system after the US Constitution was adopted. For the most part we continued to follow English Common Law. Ironically, many new laws which are established by parliaments, legislatures, executive agencies, courts, etc. are created in ignorance of, and often to the detriment of, the existing body of law, especially the common law. Conservative efforts often harm the law by elevating private, special interests above the general welfare. Liberal efforts often harm the law by trying to reform a legal system they don’t adequately appreciate or understand, and by putting the structural cart of law before the functional horse of human behavior.

Upper portion of Hammurapis’ stela (Wikimedia)

When activists, political thinkers, and economists criticize the mainstream conventions of property ownership they often fail to realize that they are objecting to various implicit defaults and assumptions about ownership in common practice today. But those customary defaults are by no means the only arrangements permitted and protected under most modern legal frameworks.

The terms and conditions of a specific transaction or instance of ownership may be codified in legal terms and placed in deeds, titles, contracts, etc.. “Standard” legal language is used to convey the standard, default assumptions. But alternative, atypical terms and conditions of ownership can be legally codified as well — without any structural changes in our legal, political, or economic systems. Activists and reformers often blame a legal system they may not adequately understand for the ways in which the system is most commonly being used by the individuals and interest groups in society.

In other words, ownership problems may be rooted more in the philosophy, psychology, and behavior of individuals, groups, and cultures than in the technical structure of our legal systems– at least that seems to be the case in the modern Western nations I am most familiar with.

Our oldest known legal code is the Code of Hammurabi — a Babylonian law code of ancient Mesopotamia, dating back to about 1772 BC and found on the Hammurapis’ stela. “Nearly one-half of the Code deals with matters of contract, establishing, for example, the wages to be paid to an ox driver or a surgeon. Other provisions set the terms of a transaction, establishing the liability of a builder for a house that collapses, for example, or property that is damaged while left in the care of another. ” (Wikipedia)

Here are some samples of conditional property laws from the Code of Hammurabi:

36. The field, garden, and house of a chieftain, of a man, or of one subject to quit-rent, can not be sold.

37. If any one buy the field, garden, and house of a chieftain, man, or one subject to quit-rent, his contract tablet of sale shall be broken (declared invalid) and he loses his money. The field, garden, and house return to their owners.

38. A chieftain, man, or one subject to quit-rent can not assign his tenure of field, house, and garden to his wife or daughter, nor can he assign it for a debt.

39. He may, however, assign a field, garden, or house which he has bought, and holds as property, to his wife or daughter or give it for debt.

[Hammurabi’s Code of Laws Translated by L. W. King]

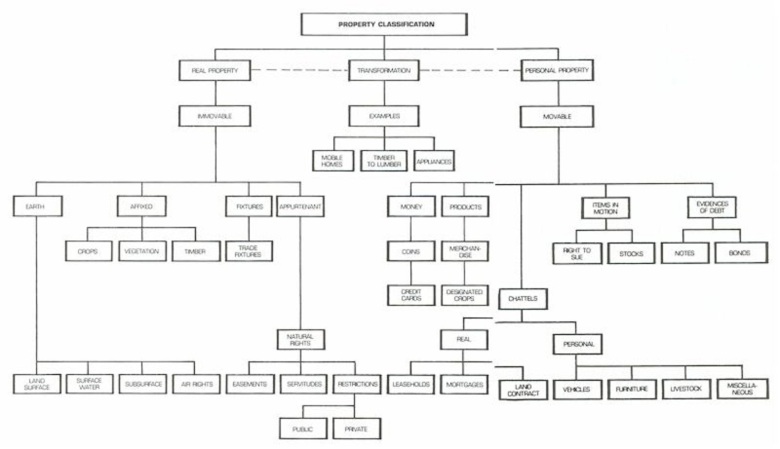

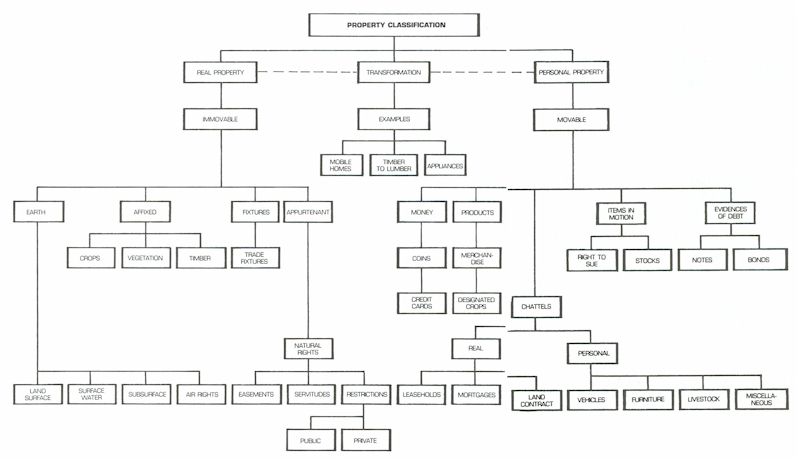

Under Western legal systems (that evolved largely from English common law and Roman civil law), ALL ownership is conditional. The relationship between an owner and the thing that is owned is a form of custody.

Despite what we naively call “absolute” private ownership, the entire bundle of property rights is never held by any one owner. There are always multiple stake-holders with legal and equitable interests in any resource, even when the majority of the bundled rights are in the custody of a private owner. One interest that is always present, both in law and equity, even when temporarily delegated to private custodians, is the public interest. The public interest includes public health, the public welfare, the sustainable viability of the ecosystem, and the interests of future generations, among other things.

Bundle of rights likened to a bundle of sticks (Wikimedia)

A private owner who holds a deed to property that conveys what in the US we call a “clear, unencumbered, fee-simple absolute title” is nonetheless subject to the rights of others to have unobstructed views, access to other property, or a neighborhood free of public hazards and nuisances. There are literally dozens of rights that others may have to or over some aspect of my private property.

In ancient times, one of the stakeholders that was always included in any ownership arrangement , even if only implicitly, was the king (and sometimes a deity). That is the origin of the legal doctrine of conditional property ownership. Today however, in modern Western societies, the legal rights and equity interests once reserved by a sovereign or deity are now vested collectively in we, the people.

As a blogger comments at Commoning, “All property relations are conditional – the concept of absolute ownership is an idea that serves a logical function in some liberal jurisprudence and a misleading rhetorical device for various uninformed libertarians with no social conscience.”

The principle of conditional property ownership is explicit by contract or implicit in many of our legal doctrines, such as:

Ironically, Western legal systems are doctrinally and structurally more aware and protective of these third-party and public interests than are most of those who use the system to conduct their business and enforce their property rights (and most of those who criticize the legal system for the sins of those who use it antisocially).

A liberal defense of private property

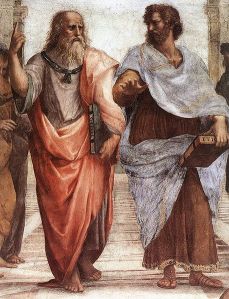

The concept of private property, like a stone axe, a hammer, or a gun, has utility even if it can also be abused. Aristotle writes, in Politics:

“For that which is common to the greatest number has the least care bestowed upon it. Everyone thinks chiefly of his own, hardly at all of the common interest; and only when he is himself concerned as an individual. For besides other considerations, everybody is more inclined to neglect the duty which he expects another to fulfill; as in families many attendants are often less useful than a few.”

This is not armchair philosophy. It it something we have all seen in our own lives. Certainly there are exceptions, but what Aristotle describes is as close to a law of human nature as I know. I have often seen it play out among family members, friends, co-workers, and commune members.

In some Soviet state-run farms, individuals and families were given small plots to grow their own food. It turned out that the productivity per acre was far greater on those hand-tended private plots than in the large fields where the latest scientific methods were used. “The size of the private plot varied over the Soviet period but was usually about 1 acre (0.40 ha). … However, the productivity of such plots is reflected in the fact that in 1938 3.9 percent of total sown land was in the form of private plots, but in 1937 those plots produced 21.5 percent of gross agriculture output.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kolkhoz

Plato (left) and Aristotle (right), a detail of The School of Athens, a fresco by Raphael. Aristotle gestures to the earth, representing his belief in knowledge through empirical observation and experience, while holding a copy of his Nicomachean Ethics in his hand, whilst Plato gestures to the heavens, representing his belief in The Forms. (Wikipedia)

Aristotle says further:

“It is evident then that it is best to have property private, but to make the use of it common… And also with respect to pleasure, it is unspeakable how advantageous it is, that a man should think he has something which he may call his own; for it is by no means to no purpose, that each person should have an affection for himself, for that is natural, and yet to be a self-lover is justly censured; for we mean by that, not one that simply loves himself, but one that loves himself more than he ought; in like manner we blame a money-lover, and yet both money and self is what all men love. Besides, it is very pleasing to us to oblige and assist our friends and companions, as well as those whom we are connected with by the rights of hospitality; and this cannot be done without the establishment of private property, which cannot take place with those who make a city too much one [referring to Plato’s idea of the ideal Republic (city) holding all property in common]; besides, they prevent every opportunity of exercising two principal virtues, modesty and liberality. Modesty with respect to the female sex, for this virtue requires you to abstain from her who is another’s [referring to Plato’s idea for the Republic’s ruling class to hold all their wives and children in common]; liberality, which depends upon private property, for without that no one can appear liberal, or do any generous action; for liberality consists in imparting to others what is our own.” (Aristotle, The Politics, II.v.)

It is very interesting that Aristotle says “it is best to have property private, but to make the use of it common.” He goes on to extol the virtues of sharing and hospitality, and to propose that they are virtues only thanks to private property. Elsewhere he talks about using universal education, and not collective ownership as Plato proposed, to achieve the common good.

By defending private property I am not suggesting that Garrett Hardin’s “tragedy of the commons” is inevitable. Far from it. Few commoners are as stupid as Hardin seems to think. In most cases commoners understand that their enlightened self-interest lies in protecting the commons from abuse and managing it sustainably. Even if they neglect their own responsibilities to the commons and cause problems, others are likely to intervene. Self interest will move us to regulate each other if not ourselves.

Nor am I suggesting that all property should be private. The public interest is best served by a diversity of conditional ownership relations for different applications, and even a diversity of ownership forms for the same applications. For example we should probably have a combination of private farmland, community farmland, and national farmland. On the other hand, we should probably not, as a rule, have private wetlands, coal mines, or oil fields. But here again, few rules are without exceptions, as in the case of the Nature Conservancy‘s wetland holdings. The Nature Conservancy is a private corporate entity that purchases and encloses natural habitats and excludes spoilers.

One thing that Aristotle never contemplated was the form of “private” ownership practiced by capitalists and their immortal and often trans-national corporations. The virtues that private ownership may promote in people and communities are entirely absent from balance sheets and quarterly reports. The perpetual and amoral ownership by capitalist corporations is so different from the kind of conditional private ownership practiced by people that it should have another name. It should probably be called property tyranny.

The biggest problems associated with ownership are not about privacy, enclosure, or exclusion per se but about the degrees, arrangements, and durations of those things. Both private and public enclosure of property can work for or against the public interest depending on the circumstances. Something I like to call “preemptive enclosure” is a means of using conditional enclosure of the commons, by the commons, for the commons. Conservation easements, land trusts, and Creative Commons copyrights are just a few examples.

In my opinion it is not in the public interest for the majority of land or durable property in a state to be held in direct public ownership. I agree with Aristotle that individual custody and stewardship of property promotes moral virtues. It is also consistent with the principle of subsidiarity. The Oxford English Dictionary defines subsidiarity as the idea that a central authority should have a subsidiary function, performing only those tasks which cannot be performed effectively at a more immediate or local level. This especially applies to the custody and management of property where absentee ownership is one of the most common sources of problems. Private ownership is still always subject to conditions (via common, statutory and administrative law) to protect public interests such as public safety, conservation, and sustainability.

Structure (law) vs practice (application)

In my opinion the greatest problems of ownership in practice are:

- absentee, idle, or disinterested ownership

- extractive ownership

- ownership in perpetuity

- excessive concentrations (actually just another variety of absentee ownership)

None of these are entirely structural (that is, dictated by our legal or economic system). They are behavioral as well.

The legal and institutional structures of society are formalized, normative reflections of the aggregate psychology (implicit associations, cognitive and cultural biases, assumptions, etc.) and behavior of the people. The structures of society have a degree of normalizing influence, but if the structures are changed without the underlying cultural assumptions and biases being changed, the old behaviors will tend to return. For example, a revolution or redistribution of wealth may only have a temporary effect– the previous social, political, or economic disparity may re-establish itself within the new structures, adapting the new structures to the old behaviors. History is full of examples, including the US “experiment in democracy”, which has come “full circle” from a revolution against a partnership between the British Crown and the East India Company (and other “royal-chartered” mercantile monopolies) to our present domination by a corrupt political class in partnership with global corporations.

Abolishing private property or redistributing wealth by structural reform alone might possibly result in an eventual return of the same behaviors in new structural guises. On the other hand, changing our practice within the existing legal framework would probably result in a gradual change of the structural framework to reflect our new behavioral norms, almost as a matter of course.

However, promising new styles or designs of conditional ownership are gradually being introduced into public awareness. One example is called “generative ownership:”

“[Generative] ownership designs are aimed at generating the conditions where all life can thrive. From the Greek ge, generative uses the same root form found in the term for Earth, Gaia, and in the words genesis and genetics. It connotes life. Generative means the carrying on of life, and generative design is about the institutional framework for doing so. The generative economy is one whose fundamental architecture tends to create beneficial rather than harmful outcomes. It’s a living economy that has a built-in tendency to be socially fair and ecologically sustainable.

“Generative ownership designs are about generating and preserving real wealth, living wealth, rather than phantom wealth than can evaporate in the next quarter. They’re about helping families to enjoy secure homes. Creating jobs. Preserving a forest. Generating nourishment out of waste. Generating broad well-being.” (Majorie Kelly, The Emerging Ownership Revolution)

Our existing legal framework has many mechanisms for protecting the commons, but we often fail to use the legal tools we have at our disposal. We sit by while corrupt regulators give away public property and resources to corporations. Why? Our legal system does not dictate that. Could our addiction to cheap energy and consumer goods have anything to do with it? We could encourage private property owners to trade various kinds of rights to their properties in exchange for tax breaks. Or we could impose tax penalties or fines on owners who mange their property in ways that harm the public good. Why don’t we do this more intensively and consistently? Could our lifestyles have more impact on our environment and our economy than our legal system does?

Intellectual Property (IP)

In the domain of intellectual property (IP), the traditional, default form of ownership of creative or intellectual works was “all rights reserved”. Ironically, those very terms expressed the idea that individual rights (plural) made up a bundle of rights that could be separated and distributed among various stakeholders. Eventually, within the existing framework of copyright law, conditionality of ownership came to be explicitly defined by various forms of conditional copyright such as the GNU General Public License or Creative Commons license. Organizations like GNU and Creative Commons perform a valuable public service by codifying formerly atypical forms of IP ownership in legally defensible terms (largely a question of adequate specificity and formality) and making those well-crafted legal templates available for public use.

(via Wikipedia)

It is crucial to understand that those new forms of copyright grew out of practice conducted under the existing legal framework. The existing framework was extended (to the extent it changed at all) in a direction established by practices adopted in the free/open software community. We did not make legislative changes to the copyright framework which then unleashed new forms of enlightened social behavior.

However…at the same time that free/open communities and peer-production communities have been hacking copyright for the benefit of the commons, the corporate world, especially big entertainment, has succeeded at introducing novel structural defects into the copyright law framework–excessive durations, unreasonable fair use limitations, disproportionate penalties for infringement, and inadequate forms of due process in enforcement. They are structural defects because they undermine the public interest in favor of predatory and monopolistic corporate interests and there are few if any short-term behavioral remedies or alternatives short of opting out of participation in the production and consumption of corporate media content. This is a very limited remedy under the current conditions of monopolization of the industry. Appropriate structural remedies would include breaking up the media monopolies and returning the terms and scope of copyright and fair use to something like their original specifications, thus restoring greater conditionality. The new forms of “industrial strength” copyright law are recent inventions that break with all former legal doctrine. Unlike the commons-oriented copyright extensions which are consistent with conditional property traditions, the industry IP proposals aim at near-absolute exclusive ownership of IP in perpetuity. The introduction and persistence of such structural aberrations depend on the corruption of our political and judicial institutions. Both have become captive to global monopoly capitalism. Thanks to its excessive concentration of wealth, global monopoly capitalism is sometimes able to assert its preferred legal framework — might makes right — over that of the people.

In the absence of a successful structural defense or reform of the copyright framework, the commons-oriented community may have little alternative but to opt completely out of the corporate media framework. In the long term the creative, co-operative working class has the skills and abilities to build an entire media counter-economy and infrastructure from the ground up. In that event we can one day turn to the old media industry and say “Be my guest–keep all your crappy IP to yourself.”

Atlantic salmon. Salmo salar. (Wikipedia)

But patents are another story. Biotech moguls like Monsanto are patenting genetically engineered (GE) and genetically modified (GM) organisms and then loosing them upon the world to spread their Frankenstein IP far and wide. Once their patented-gene-carrying pollen infects your organic corn, soy, or alfalfa your crop may belong to them. Indian farmers tried to tell Monsanto to shove their mutant seeds only to find natural seeds and seed saving outlawed by trade agreements and treaty (WikiLeaks has documented US State Department diplomats working directly for Monsanto). Next it will be GE/GM animals like transgenic salmon that will “escape” into the wild (accidentally, of course) to infect wild populations with patented genes.

That makes the increasingly popular corporate practice of trademarking ordinary English words like “face” seem almost innocuous by comparison.

Needless to say all of this flies in the face (oops) of common law and common sense. Remedies to protect the commons and the public interest from this Trojan-IP invasion will almost certainly need to be served with a side-order of civil disobedience.

Real Property

In the case of real estate and other tangible property the conditionality of ownership can be asserted through deed restrictions, covenants, easements, trust agreements, purchase and lease agreements, contracts and other means. Such arrangements are strongly supported by US courts if the terms are adequately specified and formalized. Many states now have legislatively created conservation easement programs and trusts for various public assets. But such things are perhaps more commonly implemented by non-governmental organizations like nature conservancies, community land trusts, non-profits, worker cooperatives, and individual philanthropists. If the legal framework has changed at all, it is only to the extent that practice has paved the way.

It is our footpaths, as more and more of us practice a new kind of behavior, that gradually are trodden into law. It is easy to make the logical and philosophical error that behavior follows law, that the law prescribes and constrains our behavior, because that is often our most personal, proximate, and visceral perspective. But the reverse is true. Our collective behavior, over generations and eons, becomes structurally crystallized in our laws and institutions. To change our laws in the right way, the natural and organic way, we must first change ourselves and our practice.

However, there are several practical (not structural) obstacles to the wide use of atypical conditional property arrangements for types of property other than IP (although atypical IP probably had similar issues early on). One problem is related to purchases and investments financed by third parties such as banks, retail finance companies, mortgage companies, and venture capital firms. The middlemen in property transactions tend to be very conservative about the conditionality of ownership. They want to retain as much of the bundle of rights that law and custom allows until the mortgage or other credit terms are satisfied. It may only be after a property transaction is “paid in full” that a purchaser will be free to define an atypical distribution of rights for the property in question. This situation will change as atypical transactions and ownership models become more common, and as more investors and financial middlemen come to understand and tolerate such arrangements (or in the case of public-spirited institutions, even to favor them).

Another major problem is the shortage of attorneys who are familiar with atypical property ownership models and the range of legal instruments that can be used to implement alternative forms of conditional ownership that serve the public interest and the commons. My work in the 1970’s researching the legal foundations for conservation easements and community land trusts exposed me to the lack of depth in property ownership expertise that existed in the legal and philanthropic communities. My recent exposure to the history of the Daniel Pennock Democracy School and the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF) convinces me that the situation has improved but little in the past three or four decades. Hopefully that is finally about to change with the CELDF’s new programs and other “Law of the commons” projects that are in the making.

The real tragedy of the commons

Those parts of our legal system that deal with the law of the commons and conditional property ownership are weak or rusty not by design but from disuse. Whose fault is that? Is it a failure on the part of bad, selfish, and greedy people? Sure. But it is also a failure of progressives and liberals (including liberal lawyers, judges and scholars) who are well-intentioned but legally naive and who fail to look outside the box of prevailing legal norms.

In addition to the behavioral issues I’ve mentioned, there are clearly some real structural defects in our legal framework that have accumulated through the influence of powerful and corrosive special interests on our political and judicial system. Examples are the perverse trends in commercial IP law, industry-rigged environmental and regulatory law, and the unprecedented doctrine of corporate person-hood with its perpetual ownership and freedom from inheritance tax liability. All this stuff is relatively new in legal history and it has happened on our watch.

“It is not wrong to say that the nature and intent of a society reveal themselves in the legal and customary concepts of property held by the various members and classes of that society. These property concepts do not change without an incipient or fundamental change in the nature of the society itself. The history of property relations in a given society is thus, in a way, the history of the society itself .” (Schurmann 1956: 507, Properties of Property: A Jurisprudential Analysis)

Our ancient legacy of conditional property law is well known to capitalists, and they are actively chipping away at it all the time. Few liberals even know this body of law exists, but the common law is as much a part of our commons as our creative works and our ecosystem. And we are sorely neglecting it. Whose fault is that?

If you want to be a steward of the commons, it will help to begin with some knowledge of the common law of ownership. The resources below are some of the best places I know to start.

Poor Richard

Related posts on PRA 2.0

Important Resources

Public Trust Doctrine

The public trust doctrine has its roots in the ancient Roman concept of natural law that held certain things, including the shores of water, were by their nature common to all. Opinion of the Justices (Public Use of Coastal Beaches), 139 N.H. 82, 87 (1994).

The doctrine was adopted under English common law that the tidelands and navigable waters were held by the king in trust for the general public. Id. These public rights were vested in the colonies of America, and following the American Revolution, all the rights of the king vested in the several states, subject to the rights surrendered to the national government by the Federal Constitution. Shively v. Bowlby, 152 U.S. 1, 14-15 (1894).

New Hampshire holds in trust its lakes, large natural ponds, navigable rivers and tidal waters for the use and benefit of the people of the State. State v. Sunapee Dam Co., 70 N.H. 458, 460 (1900). Navigability is not the sole test of whether a river is held in trust, but “when a river or stream is capable in its natural state of some useful service to the public because of its existence as such, it is public. Navigability is not a sole test, although an important one.” St. Regis Paper Co. v. New Hampshire Water Resources Board, 92 N.H. 164, 170 (1942). With regard to large ponds, the Supreme Court adopted a portion of the Massachusetts Ordinance of 1647 to find that a “great pond…containing more than 10 acres of land” is included with the public trust. Concord Manufacturing Co. v. Robertson, 66 N.H. 1, 26 (1889), See also RSA 271:20 (defining state-owned public waters to include all natural bodies of fresh water having an area of 10 acres or more).

The uses and benefits subject to the public trust are not limited to navigation and fishery, but include other benefits. Various cases have held that the public trust encompasses “all useful and lawful purposes”, “what justice and reason require”… See Opinion of the Justices, 139 N.H. at 90-91. http://des.nh.gov/organization/divisions/water/wmb/rivers/instream/documents/ag_opinion.doc

Property, Commoning and the Politics of Free Software by Massimo De Angelis and J. Martin Pedersen (@|Commoning|, excerpted from The Commoner, Issue 14, Winter 2010)

“In legal and philosophical terms, property relations are relations between people with regard to things. In this way, the organisation of a commons is encoded in its property rules, which structure its use, access and decision-making rights and responsibilities accordingly. Property, then, is central to debates about commons and commoning: how do commoners relate to each other with regard to a given resource (land, code, rivers, forests, hills, cars) and how is a commons defined vis-a-vis the rest of the world? Questions such as class, gender and other hierarchies, environmental justice, sustainability and spirituality are relevant here. Most of these social dynamics – most of the time, even on the “outside of capital”– turn on property relations: who has access to what (tools, resources, land), when and under what conditions, who gets to decide and how are decisions made?

“Often, however, property is juxtaposed to commons – as if commoning was a negation of property. Unfortunately, this view presupposes and consolidates a very narrow understanding of property, where the general is conflated with the particular. Property relations are not only exclusive, private property rights as instantiated within capitalist democracy (that is, a particular conception of property). As a jurisprudential concept, property can be used to understand, analyse, reflect upon and organise social relations with regard to things in any context (this is the general conception of property). The conflation of the general with the particular, which conceals the historical and anthropological fact that property can be and is understood (very) differently, takes on a further dimension in colloquial talk. We have come to accept that property is stuff: things that we own, and that we own exclusively. As a rhetorical device in privatisation arguments it is very powerful because it invokes feelings that are close to home, literally. We say things like “this house is my property”.

“Similarly, privatisation arguments in the context of immaterial goods and resources invoke the same passions and feelings: this text or this source code “is the property of Microsoft”. Such a conception of property is not only a conflation, but furthermore hides the complexity of the social relations that property arrangements circumscribe and give rise to.

“It is obvious that social, cultural and political practices define any given property regime, hence analytically exploring property relations gives us an insight into the relation between the socio-cultural and the law. It is precisely at this level that commons are created and organised – and through the language of property we can articulate practices of commoning into property protocols (rules and agreements) that can provide stability of the commons on the inside and protection against threats of capital’s enclosure from the outside. Self-determination and autonomy begins by taking the law into your own hands. (Property, Commoning and the Politics of Free Software)

Properties of Property: A Jurisprudential Analysis (pdf), by J. Martin Pedersen (The Commoner, Issue 14, Winter 2010)

“No doubt the eighteenth century preferred rational treaties expounding the theory of property to

historical essays describing the theories of property. But … we … know that the institution of property

has had its history and that that history has not yet come to an end … We begin with the knowledge

that there must be as many theories of property as there have been systems of property rights.

Consequently we abandon the search for the true theory of property and study the theories of the past

ages. Only thus can we learn how to construct a theory suitable to our own circumstances” (Schlatter

1951: 10).

Property Rights in the Commons: The ubiquity of mixed systems (extracts from Ostrom’s Law: Property Rights in the Commons)

Ostrom’s Law: Property Rights in the Commons, Lee Anne Fennell (University of Chicago Law School) International Journal of the Commons, Vol 5, No 1 (2011).

The Commentaries and and some of Blackstone’s other work is the main source of my background in common law. I poured over Blackstone for nearly a year while I was researching the legal foundations for community land trusts and conservation easements. This is probably the greatest single record and repository of humanity’s common legal heritage and it is easily readable by educated laypeople. Various abridgements and online texts are available.

“The Commentaries were long regarded as the leading work on the development of English law and played a role in the development of the American legal system. They were in fact the first methodical treatise on the common law suitable for a lay readership since at least the Middle Ages. The common law of England has relied on precedent more than statute and codifications and has been far less amenable than the civil law, developed from the Roman law, to the needs of a treatise. (Wikipedia/Commentaries)

“When the Commentaries were first printed in North America (1772) 1,400 copies were ordered for Philadelphia alone. Academics have also noted the early reliance of the Supreme Court on the Commentaries, probably due to a lack of US legal tradition at that time. Robert Ferguson notes that “all our formative documents — the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, the Federalist Papers and the seminal decisions of the Supreme Court under John Marshall — were drafted by attorneys steeped in Sir William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England. So much was this the case that the Commentaries rank second only to the Bible as a literary and intellectual influence on the history of American institutions”. Even today, the Commentaries are cited in Supreme Court decisions between 10 and 12 times a year.

“Within United States academia and practise, as well as within the judiciary, the Commentaries had a substantial impact; with the scarcity of law books on the frontier, they were “both the only law school and the only law library most American lawyers used to practise law in America for nearly a century after they were published”. Blackstone had drawn up a plan for a dedicated School of Law, and submitted it to the University of Oxford; when the idea was rejected he included it in the Commentaries. It is from this plan that the modern system of American law schools comes. Subscribers to the first edition of Blackstone, and later readers who were profoundly influenced by it, include James Iredell, John Marshall, James Wilson, John Jay, John Adams, James Kent and Abraham Lincoln.” (Wikipedia/Blackstone)

Related Resources

- Ostrom’s Law: Property Rights in the Commons “Elinor Ostrom’s work has immeasurably enhanced legal scholars’ understanding of property.” (International Journal of the Commons)

- Property Rights in the Commons: The ubiquity of mixed systems (extracts from Ostrom’s Law)

- ‘Properties of Property: A Jurisprudential Analysis‘, The Commoner, Special Issue, Volume 14, Winter 2010, 137-210.

- Bringing the Power of the Law to Environmental Stewardship, The Common Property Rights Project (thwink.org)

- Sustainable Economies Law Center SELC aims to help social enterprises, worker-owned co-ops, and other mission-oriented enterprises sort through legal red tape.

- Property, Commoning and the Politics of Free Software by Massimo De Angelis and J. Martin Pedersen ( The Commoner, Issue 14, Winter 2010)

-

Generative vs. Extractive Ownership (p2pfoundation.net)

- Benjamin Franklin to Robert Morris on taxes and private property 25 Dec. 1783

- Do judges make law in common law countries (wiki.answers.com) An “activist” judge is a judge you don’t agree with.

- Equity (law) Equity is the name given to the set of legal principles, in jurisdictions following the English common law tradition, that supplement strict rules of law where their application would operate harshly. In civil legal systems, broad “general clauses” allow judges to have similar leeway in applying the code. Equity is commonly said to “mitigate the rigor of common law.”

- “Recalibrating the Law of Humans with the Laws of Nature: Climate Change, Human Rights and Intergenerational Justice” by Burns H. Weston and Tracy Bach (Vermont Law School & University of Iowa: Climate Legacy Initiative, 2009).

- Green Governance: Ecological Survival, Human Rights, and the Commons, (Commons Law Project)

- Commons in a taxonomy of goods (blog.p2pfoundation.net)

- Hammurabi’s Code of Laws Translated by L. W. King

-

The Community land trust handbook Institute for Community Economics. Published 1982 by Rodale Press

- Possession as the origin of property, Carol M. Rose, Yale Law School

- Articles on land rights history in the UK

Organizations and Websites focusing on “The Commons”

- The Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund CELDF works with communities to establish Community Rights – such that communities are empowered to protect the health, safety, and welfare of their residents and the natural environment, and establish environmental and economic sustainability.

- Democracy School Online, (The Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund)

- The School of Commoning “a growing worldwide community of people participating in the global and local commons. We support the developing commons movement, as well as interested organizations and individuals, with well-organized knowledge resources and educational programs on commoning and the commons.”

- International Journal of the Commons “The International Journal of the Commons (IJC) is an initiative of the International Association for the Study of the Commons (IASC). As an interdisciplinary peer-reviewed open-access journal, the IJC is dedicated to furthering the understanding of institutions for use and management of resources that are (or could be) enjoyed collectively. These resources may be part of the natural world (e.g. forests, climate systems, or the oceans) or they may emerge from social realities created by humans (e.g. the internet or (scientific) knowledge, for example of the sort that is published in open-access journals).”

- On the Commons/Commons Magazine “a network of citizens and organizations that champions the cause of the commons on many fronts. Our mission is to advance a new worldview by naming, claiming, protecting and expanding the commons for the good of all.”

- Commons Law Project “We must find new ways to protect our planet from the unsustainable growth imperatives of neoliberal economics and politics. This will require a new architecture of “green governance”―laws, public policies, and social practices that can honor human rights and commons-based management of natural resources large and small…”

- The P2P Foundation, Category:Commons “What we share. Creations of both nature and society that belong to all of us equally, and should be maintained for future generations. The Commons has the potential to replace the commodity as the determining form of re-/producing societal living conditions.”

- Helene Finidori’s Blog “Rethinking Sustainable Development in terms of Commons.” Helene is a trail blazer.

- Commoning (blog) ~ property relations and the architecture of commons ~ (appears to be inactive now but contains a lot of excellent material, especially on property law)

- Democracy School Online, (The Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund)

Church of Reality

Church of Reality Critiques Of Libertarianism

Critiques Of Libertarianism P2P Foundation

P2P Foundation Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy The Stone

The Stone