Exegesis on Poor Richards’s Hex Model

In the “Ownership of the Commons” and a few previous comments in the P2P Group on Facebook I introduced the “Hex Model” framework:

people-places-things — relations-rules-results

The hex model was inspired by an essay by Helene Finidori, Systems Thinking and ‘Commons-Sense’ for a Sustainable World . There are probably other things like it out there, because it is practically a self-evident concept. It applies retroactively to everything I’ve written and read in the past few years on the commons, property, ecological economics, and similar topics. I would like to continue developing this concept through dialog here or in the P2P group.

Basically the hex model applies to all topics that consider relations between people in which any kind of resource is important. If something pertains to people and to resources at the same time, the hex model applies.

A six-pointed star formed by extending each of the sides of a regular hexagon into equilateral triangles.

The first triangle of the hex model hexagram are “objects”: people-places-things. These are variables that can be given concrete values taken from in vivo and in situ cases.

The second triangle combines two sets of algorithms and a set of results. The relations-rules-results are also taken from the same specific cases as the people-places-things.

Taken together, these elements and their arrangement may be used to model actual cases of socioeconomic activity. These elements can be arranged like an equation in which the object variables are represented along with some arrangement of relations and rules. Any of the elements might appear on either side of the equation, but the expression on the left of the ” = ” would generally be the “inputs” and the expression on the right of the ” = ” would typically be the “output” or results.

I am trying to develop a common, generic scaffolding for organizing key particulars and metrics for the analysis of human-resource relations that will work across a variety of ontologies or idioms. Possession, access, ownership, authority, governance, control, and management might be thought of as similar things expressed in different idioms or seen from different perspectives. Control of property or resources (and commensurate responsibilities), is often distributed across various levels from state to community to group to individual. In most cases we find some degree of subsidiarity in these relations. But without appropriate and consistent models and data structures it can be difficult to compare, contrast, or quantify these things in any rigorous way, especially across different researchers, writers, activists, and domains.

In this particular formulation, as first framed, I did not see the hex model as prescriptive of practice except for analytical and rhetorical practice. The original aim was to capture particularities in commoning practice or any other in vivo and in situ socioeconomic practice and then analyze, contrast, compare, and discuss these particularities in a more rigorous way than is usually found in colloquial discourse and perhaps in some academic discourse. At least we can aim at some terminology that might remain relatively coherent across multiple communities of interest.

But this just in…

Helene Finidori has suggested some adaptations of the hex model that might make it more applicable to “‘seeding’ or ‘domesticating’ emerging change,” or in other words to commoning practice rather than simply to analysis and rhetoric. Her suggestion consists of renaming and rearranging the elements of the hex model as follows:

People-Domain (environment)-Interactions: This would form the first triangle and would “cater for virtual operations (think specification of boundaries of the commons or the system)”. (HF) Helen argues that “this is the relational context in which the emergent behavior arises, that can be ‘seeded’.”

Things (objects/assets)-Rules(culture)-Results: This forms the second triangle of elements that “make up the commons (as I described them), as outputs that can be measured, what is ‘produced’ by the emergent behavior of the system and become inputs as medium for interaction in the relational context in a feedback loop.” (HF)

I admit to some reluctance to abandon the “people, places, and things” triad precisely because it is a preexisting, familiar meme; but Helene’s suggestions have compelling force. I especially like the feedback loop or spiral perspective in which inputs become outputs and then feed back as new inputs.

At least it remains a HEX model, thank goodness, as I was quite attached to that. 🙂

But no worries for Poor Richard. Michael Maranda pulls all my old chestnuts (and perhaps some future ones) out of the fire with this compact gem:

“Interesting to consider the original triad groupings and the [Finidori] alternate that resulted from the discussion. As triads go, we don’t lose anything, because taking one triad or a different combination will be a matter of what facets are relevant for a given approach or in making particular points.” ~Michael Maranda

Nice save.

The hex model is really just a little high-level template for data. We have established that it can be permutated and instantiated in different ways to suit various ontologies or purposes. Of course when you actually get down to particulars at a level of granularity (a unit of land with various appurtenances, or an adequate functional description of a person, for example) many additional sub-categories and data structures would be required and many additional standards and specifications would be needed.

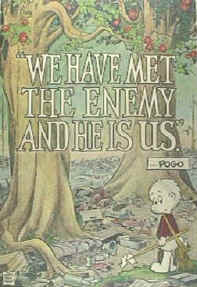

And now this is thrown open to the nascent commons community, to its critics, and even to the maddening crowd for comments, questions, and collaboration–a consummation devoutly to be wished.

Poor Richard

Resources, events, agents (REA) is a model of how an accounting system can be re-engineered for the computer age. REA is an ontology. The real objects included in the REA model are:

- goods, services or money, i.e., resources

- business transactions or agreements that affect resources, i.e., events

- people or other human agencies (other companies, etc.), i.e., agents

Church of Reality

Church of Reality Critiques Of Libertarianism

Critiques Of Libertarianism P2P Foundation

P2P Foundation Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy The Stone

The Stone

October 13, 2012 at 6:56 am

I appreciate your approach and thank you for the reference to Finidori’s work! It seems to me that the morphogenetic field is expanding and a global, holistic commons-oriented understanding of property relations is emerging.

Here are, it seems to me, further details to the convergence of our thought patterns:

From: “Properties of Property: A Jurisprudential Analysis” (http://commoning.wordpress.com/essay/ )

2.1 Introduction: sovereigns, commoners and the state we are in.

In this chapter I provide the reader with a framework that enables an analytical understanding of property. I argue that property is normative protocols structuring social relations with regard to things (that is, property relations). Given that there are, in practice, no social relations that do not involve things of some kind as their setting or as their props, property is of fundamental importance to the way in which societies, and other social groups, are organised. Property protocols refer to customs, norms, and conventions guiding people’s behaviour. These protocols (often understood as patterns of duties, rights, powers, privileges and so on) define certain freedoms or limitations with regard to who may do what with any given thing or resource.

2.1.1 Private property and commoning under one umbrella.

The most well-known and widespread configuration of property is private property, which, of course, characterises capitalist democracy. Private property is a particular property protocol that is generally understood as giving rise to social relations with regards to things that are paradigmatically different from the social relations with regard to things that I have referred to as commoning, following Linebaugh and De Angelis.

While it is uncontroversial to define property as social relations with regard to things, philosophical or legal accounts of property do not normally account for commoning as property. The commons is seen as the paradigmatic non-property case. Yet both commoning and private property concern the same subject matter: how we relate to each other with regard to things and with regard to the rest of the world. Who has access to what resource, what are those with access allowed to use the resource for, who takes responsibility for the resource, what happens to the wealth that can be generated from the resources, who can sell, buy or otherwise transfer the privilege of access to a resource and its wealth effects, who makes the decisions about these things, how are the decision-making processes organised in cases where more than one individual holds the decision-making authority and, finally, with reference to what values are these decisions legitimised?

Once we uncover the elements which both share, these two different kinds of property can be brought together under one analytical umbrella. The purpose is to reveal the way in which each of them functions and the different kinds of social relations that they give rise to. In this way the applicability of either of the two in a given context – for instance a particular resource or class of objects – can be assessed on the same terms. A normative evaluation can start from there.

and so on: http://commoning.files.wordpress.com/2010/12/the-commoner-14-winter-2010-chapter2.pdf

October 13, 2012 at 12:42 pm

jmp,

Many thanks for sharing these excerpts and links to your work. The convergence is very encouraging to me, and you have stated some of the principles on which we firmly agree much better than I. We are most fortunate and gratified to have your attention and collaboration in this approach to “a global, holistic commons-oriented understanding of property relations.”

May the expanding morphogenetic field be with you,

PR

October 13, 2012 at 9:45 pm

Your hextet seems arbitrary in the same way as you point out that definitions of capitalism/socialism can be. Is a robot a person or a thing? Your body constitutes a place for other organisms, so you are a person and a place and a thing simultaneously (and a process, etc…). Does it represent a multi-dimensional coordinate system where some things have more “person-ness” than others?

There are things we perceive as things, changes in those things, and changes in our perceptions. Are perceptions the “relations” in your model?

I think the concept in your final paragraph of “Ownership of the Commons” is what Alfred Korzybski calls “confusion of orders of abstraction”. If you’re looking for some basic tools that people can use to organize together you could do worse than build upon his work. He advocated for the building of structural models which require us to integrate our limited perceptions into our understanding of reality to troubleshoot our social relations.

And speaking of social relations, why are you guys using Facebook where non-members cannot access the P2P Group? Is there some problem with the open P2P Foundation communication tools?

October 14, 2012 at 1:56 pm

Karl,

Thanks for the critique! Obviously the hex model is a vast oversimplification. It is the top level of a particular generalization or abstraction intended as a handy template. Many permutations, sub-levels, and data structures can be added.

Your questions are good ones, but answers may be out of scope for the time being. I can no more define what a person is than I can say what matter is or draw the proper line between animate and inanimate. Heuristically speaking I suspect that robots will be persons when they can assert that status for themselves.

The hex model can be revised and extended by persons using any number of assumptions, even if those are incomplete and/or contradictory. The measure of utility is fitness for a particular purpose, and lies in the eye of the beholder.

I agree that Korzybski’s ideas (e.g. “the map is not the territory”) are applicable — could you provide some quotes?

This discussion is on Facebook because that’s where it started. Now its here too. I’ll post the essay (with a better title) on the P2PF at some point, or you (or anyone) are welcome to do so.

best regards,

PR

October 14, 2012 at 8:14 pm

Science & Sanity is over 800 pages with all the forwards so I could give many quotes. It’s available online at http://esgs.free.fr/uk/art/sands.htm. I made a single PDF which concatenates all the chapter PDFs there which I can send you if you’d like.

A search for “orders of abstractions” will turn up passages such as this:

Page 166

Accidentally, some light is thus thrown on the problem of ‘evolution’. In actual objective life, each new cell is different from its parent cell, and each offspring is different from its parents. Similarities appear only as a result of the action of our nervous system, which does not register absolute differences. Therefore, we register similarities, which evaporate when our means of investigation become more subtle. Similarities are read into nature by our nervous system, and so are structurally less fundamental than differences. Less fundamental, but no less important, as life and ‘intelligence’ would be totally impossible without abstracting. It becomes clear that the problem which has so excited the s.r of the people of the United States of America and added so much to the merriment of mankind, ‘Is evolution a “fact” or a “theory” ?’, is simply silly. Father and son are never identical – that surely is a structural ‘fact’ – so there is no need to worry about still higher abstractions, like ‘man’ and ‘monkey’. That the fanatical and ignorant attack on the theory of evolution should have occurred may be pathetic, but need concern us little, as such ignorant attacks are always liable to occur. But that biologists should offer ‘defences’, based on the confusion of orders of abstractions, and that ‘philosophers’ should have failed to see this simple dependence is rather sad. The problems of ‘evolution’ are verbal and have nothing to do with life as such, which is made up all through of different individuals, ‘similarity’ being structurally a manufactured article, produced by the nervous system of the observer.

October 14, 2012 at 9:58 pm

Karl,

Thanks for the link. For purposes of searching I would definitely like the all-in-one pdf. I will try to search for some more quotes. I don’t know if I can agree with the one you gave without looking at more context. Without knowing Korzybski’s full argument about similarities, I am inclined to consider similarity (not equivalence) just as real and important as difference, although semantically not its exact complement.

PR